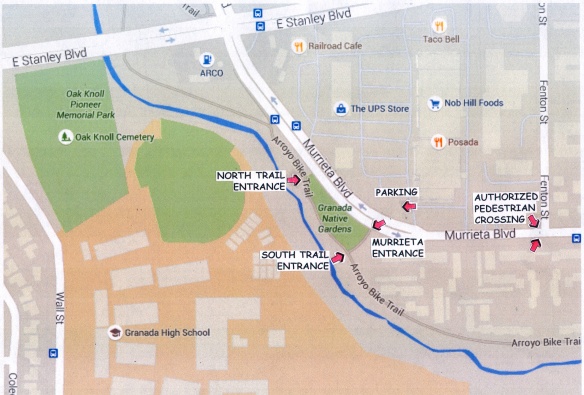

A Personal Note During our work at the Granada Native Garden, we volunteers are often approached by visitors using the adjacent Arroyo Mocho Bike Trail who thank us for our labors in maintaining the Garden. Many also appreciate the colorful display of wildflowers in the Garden in the springtime.  However, I suspect that many of these passersby have never actually entered the Garden and wandered thru it casually to appreciate the different colors, shapes, smells and subtleties present in this tiny sample of native California, and can be appreciated at any time of the year, not just in the spring. Not to mention the many plant identification markers which tell about the importance of individual plants to the ecology of the region and to the Native Americans who used to live in this region and depended on the plants for their livelihood and survival. As one elderly visitor once remarked, ”You see all kinds of things here, if you just stop and look! ” The Granada Native Garden was once described by a visitor as “Livermore’s Best Kept Secret”. It is true that the GNG takes up only 1/3 of an acre of downtown Livermore, and is bounded on one side by the busy traffic of Murrieta Boulevard and on the other by the Granada High School campus.

However, I suspect that many of these passersby have never actually entered the Garden and wandered thru it casually to appreciate the different colors, shapes, smells and subtleties present in this tiny sample of native California, and can be appreciated at any time of the year, not just in the spring. Not to mention the many plant identification markers which tell about the importance of individual plants to the ecology of the region and to the Native Americans who used to live in this region and depended on the plants for their livelihood and survival. As one elderly visitor once remarked, ”You see all kinds of things here, if you just stop and look! ” The Granada Native Garden was once described by a visitor as “Livermore’s Best Kept Secret”. It is true that the GNG takes up only 1/3 of an acre of downtown Livermore, and is bounded on one side by the busy traffic of Murrieta Boulevard and on the other by the Granada High School campus.  But, small as it is, the GNG offers its visitors more than a sight for sore eyes and a tiny island of peace and serenity in the middle of a busy city. Evidence is accumulating that exposure to nature, even in brief doses, is not only healthful but therapeutic. We shall examine some of that evidence in this article. (Maybe this helps to explain why golf is so popular, especially among people who might be less likely to otherwise spend time in nature.) (Note: Most images can be enlarged by clicking on them.)

But, small as it is, the GNG offers its visitors more than a sight for sore eyes and a tiny island of peace and serenity in the middle of a busy city. Evidence is accumulating that exposure to nature, even in brief doses, is not only healthful but therapeutic. We shall examine some of that evidence in this article. (Maybe this helps to explain why golf is so popular, especially among people who might be less likely to otherwise spend time in nature.) (Note: Most images can be enlarged by clicking on them.)

Evidence from Therapy It is well acknowledged that modern life can afflict us with symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression. Especially since the dawn of the Internet, we’ve become more irritable, less sociable, more narcissistic, more distracted and less cognitively nimble. Research and actual experience in Japan, Germany and forest-rich Scandinavia has found that “forest therapy” — spending time walking in natural surroundings (as opposed to urban concrete, asphalt and traffic) — is not only good exercise, but can result in a decrease in the body’s stress hormones, blood pressure and heart rate. We would be in good company — reportedly Aristotle, Charles Darwin, Nikola Tesla, and Albert Einstein all found that walking outdoors helped them to think. The American psychologist Benjamin Rush observed that patients who engaged in physical activity often recovered more quickly than those who “languished within the walls of the hospital”. And Freud blamed cities for “unhealthy repressive tendencies”. But just within the past several years, numerous doctors, psychiatrists, educators, ecotherapists and pediatricians have witnessed significant changes in their clients’ outlook on life, after prescribing for them a habit of exposure to nature. The Japanese term shinrin yoku, or “forest bathing”, means letting nature into one’s body thru all five senses. Elements of the environment, such as sunlight, the odor of wood and foliage, the sound of running water in streams, and the colors, scenery and atmosphere of the forest can provide relaxation and mental clarity and reduce stress.  This doesn’t mean you have to move to the country. One psycho- logist recommends just 20 minutes a day outside in nature. To ward off depression, a study in Finland recommends a minimum of five hours a month in nature. Others have found that as little as five minutes in a natural setting, whether walking in a park or gardening in the backyard, improves mood, self-esteem, and motivation, even if it’s starting out with five minutes of weeding. But in a word, any time we have an opportunity to separate ourselves from a manic, urban environment, is time well spent for our mental health.

This doesn’t mean you have to move to the country. One psycho- logist recommends just 20 minutes a day outside in nature. To ward off depression, a study in Finland recommends a minimum of five hours a month in nature. Others have found that as little as five minutes in a natural setting, whether walking in a park or gardening in the backyard, improves mood, self-esteem, and motivation, even if it’s starting out with five minutes of weeding. But in a word, any time we have an opportunity to separate ourselves from a manic, urban environment, is time well spent for our mental health. Evidence from Evolution

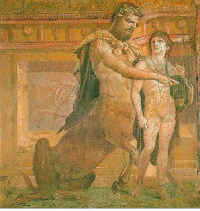

Evidence from Evolution  Our human ancestors, beginning with the genus Homo, emerged about 2-3 million years ago. Since that time, we humans have spent over 99% of our evolutionary history immersed in natural environ- ments. Our humanity has been influenced by the ability to recognize both the comforting and the hazard- ous elements of life in the natural world, and respond to them. The humans who were most sensitive to the influence of nature were likely to have passed it on to their progeny. However, we live in a society now characterized by urbanization and artificiality. We are becoming increasingly isolated from the natural world, even tho our physiological functions remain adapted it. Ludwig van Beethoven realized that “the woods, the trees and the rocks give man the resonance he needs.” Yoshifumi Miyazaki, Ph.D., a leader in promoting the salutary effects of our reconnection to nature, emphasizes that “naturalistic environments remain some of the only places where we engage all five senses and thus by definition, are fully, physically alive.” The eminent biologist and naturalist E. O. Wilson, proponent of the biophilia hypothesis, proposes that “peaceful or nurturing elements of nature help us regain equanimity, cognitive clarity, empathy and hope. The humans who were most attuned to the cues of nature were the ones who survived to pass on these traits.” While, in the past, contact with nature was inescapable and routine, our lives now are “dominated by a tech- nology which is wondrously powerful — and yet nonetheless dead.” “We are animals, and like other animals, we seek places that give us what we need.”

Our human ancestors, beginning with the genus Homo, emerged about 2-3 million years ago. Since that time, we humans have spent over 99% of our evolutionary history immersed in natural environ- ments. Our humanity has been influenced by the ability to recognize both the comforting and the hazard- ous elements of life in the natural world, and respond to them. The humans who were most sensitive to the influence of nature were likely to have passed it on to their progeny. However, we live in a society now characterized by urbanization and artificiality. We are becoming increasingly isolated from the natural world, even tho our physiological functions remain adapted it. Ludwig van Beethoven realized that “the woods, the trees and the rocks give man the resonance he needs.” Yoshifumi Miyazaki, Ph.D., a leader in promoting the salutary effects of our reconnection to nature, emphasizes that “naturalistic environments remain some of the only places where we engage all five senses and thus by definition, are fully, physically alive.” The eminent biologist and naturalist E. O. Wilson, proponent of the biophilia hypothesis, proposes that “peaceful or nurturing elements of nature help us regain equanimity, cognitive clarity, empathy and hope. The humans who were most attuned to the cues of nature were the ones who survived to pass on these traits.” While, in the past, contact with nature was inescapable and routine, our lives now are “dominated by a tech- nology which is wondrously powerful — and yet nonetheless dead.” “We are animals, and like other animals, we seek places that give us what we need.”

Evidence from Biology Plants take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and in turn release oxygen. Our brains require a steady amount of glucose and oxygen to function properly, so finding ways to increase their oxygen levels could help our brains function better. This is especially true in an environment in which automobile engines and anything that burns coal, wood, gasoline and other petroleum products replaces the oxygen in the air with carbon dioxide and monoxide. It seems logical that an environment in which oxygen-producing plants predominate is one in which our bodies function better. Likewise, it has long been acknowledged that having plants in the home can reduce carbon dioxide levels while increasing oxygen levels. Vitamin D is an essential nutrient required to maintain the health of our bones and teeth, support the health of our immune system, brain, and nervous system, regulate our insulin levels, and support lung function and cardiovascular health. While only a few foods naturally contain adequate sources of vitamin D, our bodies are able to manufacture vitamin D thru the intervention of sunlight. Time spent outdoors in nature, even for short periods of time, enables our bodies to maintain a healthy level of vitamin D. Furthermore, sunlight also appears to influence the shape of the retina in our eyes, protecting the eyeball from growing too long and causing myopia (near-sightedness). As a bonus, time spent outdoors gives our eyes the practice of focusing on features that are both near and far, (as long as our eyes are not glued to our smart phone screen). I delight in the aroma of cloves when I pass the elderberry bush in full bloom in the Granada Native Garden, or of any one of many sages growing there, or the distinctive aroma of coyote brush or a native sycamore growing along an arroyo or an open field. A great many of the phytochemicals that are produced by these and other plants are not detectable by humans, but insects and birds can sense them in the atmosphere even many miles away, and alert them to desirable food or nectar sources. These volatile chemicals are part of the air we breathe when we are surrounded by trees, shrubs, grasses, herbs and the soil. They include terpenes, pinenes, limonenes and numerous other substances with which we are already familiar in conifers, spices, mints, sages, basil, citrus fruits and even cannabis. Over the course of human evolution, native peoples have learned that numerous phytochemicals have beneficial effects on our health. The whimsical advice to “Take two hours of pine forest and call me in the morning” is very much to the point — simply walking in the woods and inhaling the atmosphere produced by plants most likely has a certain beneficial effect on our immune system and general health, and the only sense we have of it is that it feels good after a walk in nature! For more about terpenes, see the Newsletter article “Tarweeds – and Their Evil Cousin”, published on October 15, 2017.  Evidence from Fractals

Evidence from Fractals  Our brains appear to be especially well-adapted to recognize patterns. We are wired to appreciate patterns, altho we may do it uncon- sciously. We probably developed this facility because we evolved outdoors, in a world filled with an infinite number of interesting shapes, colors and configurations. There are so many variations of these patterns, also called fractals, some obvious and others subtle, that we take them for granted, and are barely aware of them. Nonetheless, our exposure to these patterns over the millenia has contributed to developing the remarkable complexity of the human brain.

Our brains appear to be especially well-adapted to recognize patterns. We are wired to appreciate patterns, altho we may do it uncon- sciously. We probably developed this facility because we evolved outdoors, in a world filled with an infinite number of interesting shapes, colors and configurations. There are so many variations of these patterns, also called fractals, some obvious and others subtle, that we take them for granted, and are barely aware of them. Nonetheless, our exposure to these patterns over the millenia has contributed to developing the remarkable complexity of the human brain.

Some examples of fractals in nature include sea shells, snow flakes, lightning, broccoli, ferns, trees and leaves, pineapples, clouds, crystals, mountain ranges, shore lines, rivers, sea urchins and sea stars, stalagmites, stalactites and icicles. According to David Pincus, Ph.D., “Fractal structure helps us to grow and connect … and has direct influences on physical health by encouraging integration and flexibility among our circulatory, respiratory, and immune systems”. Nanoparticle physicist Richard Taylor believes that “We need these natural patterns to look at, and we’re not getting enough of them.”

Some examples of fractals in nature include sea shells, snow flakes, lightning, broccoli, ferns, trees and leaves, pineapples, clouds, crystals, mountain ranges, shore lines, rivers, sea urchins and sea stars, stalagmites, stalactites and icicles. According to David Pincus, Ph.D., “Fractal structure helps us to grow and connect … and has direct influences on physical health by encouraging integration and flexibility among our circulatory, respiratory, and immune systems”. Nanoparticle physicist Richard Taylor believes that “We need these natural patterns to look at, and we’re not getting enough of them.”

It is my belief that our subliminal awareness of the patterns surrounding us in nature — in addition to the effect of the phytochemicals in the air — is responsible for the comforting, de-stressing experience that results from time spent in nature. Being surrounded by nature makes us feel at home again.

When we find reasons to withdraw from nature, or when modern life weans us from the outdoors in favor of more time spent in front of a screen or tethered to a smart phone, we deprive ourselves of the therapeutic regimen that is part of our evolutionary heritage as human beings. We become less insightful, less social, less empathetic, less human.

When we find reasons to withdraw from nature, or when modern life weans us from the outdoors in favor of more time spent in front of a screen or tethered to a smart phone, we deprive ourselves of the therapeutic regimen that is part of our evolutionary heritage as human beings. We become less insightful, less social, less empathetic, less human.

Nature Therapy at the Granada Native Garden How much nature is effective to restore our psyche? The Journal of Experimental Psychology suggests an ideal woodland of about 12 acres, at least 5 hours a month. Lisa Tyrväinen of the National Research Institute of Finland might agree that two or three days per month outside the city would work just as well. But most researchers in this field would probably agree that any amount of time spent surrounded by the effects of nature is restorative.

Murrieta Entrance

South Trail Entrance

The Bay Area has numerous sizeable woodland parks, close to most of our cities, where it would be relatively easy to escape if one were to make it a priority. The Granada Native Garden is a bit smaller (only 1/3 of an acre! ), but it is located within the city limits, so it is close at hand. On the other hand, it is bordered by a busy, noisy main thoroughfare on one side, which makes it difficult to isolate oneself from city life.

North Trail Entrance

Yet, there is much nature to experience in this small enclave. By simply walking into the Garden, you are immediately immersed in an environment radically different from the concrete, traffic and commercial world a few steps away. Better yet, sit at one of the mosaic-covered tables and try to shut the bustle of the city out of your consciousness. “You will see all kinds of things here, if you just stop and look.” If water is flowing in the nearby Arroyo Mocho, the relaxing sound of the water will help remind you that you are in a different place.  How many different structures and shapes do you see around you? How many colors? How many different hues of the same color? Are any plants in bloom? Where are they, and how do they differ from each other? Do any of the plants have fruits, in the form of seeds, pods or cones? Does it smell different here in the Garden? Are you curious about any of the things you see? Do you hear or see any bird life? What are the birds doing — gathering seeds, calling to each other, searching for food, being aware of you or of others of their type? Get up and walk around. Are any parts of the Garden more or less shady, flat or sloped, dry or moist? Do different plants grow in different parts of the Garden? Do some plants have tough, stiff leaves, while others have soft and tender leaves? Narrow, needle-like leaves or broad leaves with large surface area? How do you think the size, shape and texture of the leaves helps the plant survive in our hot, dry summers? As you walk around, notice the white markers that tell you the name of the plants, and something about how the plant is important to the environment, or how it was used by the Native Americans. How about fractals? Use your imagination, with the help of the examples displayed above, to recognize patterns in the living things around you. If you see any, I hope you photograph them and forward them to Jim at JIMatGNG@gmail.com ! As you walk around, notice the white markers that tell you the name of the plants, and something about how the plant is important to the environment, or how it was used by the Native Americans. The volunteers at the Granada Native Garden encourage you visit the Garden often and experience the restorative qualities of this small sample of nature. And to become a “Follower” of the Granada Native Garden Newsletter to keep in touch with some of the amazing features in the Garden, by clicking the “Follow” button that (usually) appears at the lower right corner of your screen!

How many different structures and shapes do you see around you? How many colors? How many different hues of the same color? Are any plants in bloom? Where are they, and how do they differ from each other? Do any of the plants have fruits, in the form of seeds, pods or cones? Does it smell different here in the Garden? Are you curious about any of the things you see? Do you hear or see any bird life? What are the birds doing — gathering seeds, calling to each other, searching for food, being aware of you or of others of their type? Get up and walk around. Are any parts of the Garden more or less shady, flat or sloped, dry or moist? Do different plants grow in different parts of the Garden? Do some plants have tough, stiff leaves, while others have soft and tender leaves? Narrow, needle-like leaves or broad leaves with large surface area? How do you think the size, shape and texture of the leaves helps the plant survive in our hot, dry summers? As you walk around, notice the white markers that tell you the name of the plants, and something about how the plant is important to the environment, or how it was used by the Native Americans. How about fractals? Use your imagination, with the help of the examples displayed above, to recognize patterns in the living things around you. If you see any, I hope you photograph them and forward them to Jim at JIMatGNG@gmail.com ! As you walk around, notice the white markers that tell you the name of the plants, and something about how the plant is important to the environment, or how it was used by the Native Americans. The volunteers at the Granada Native Garden encourage you visit the Garden often and experience the restorative qualities of this small sample of nature. And to become a “Follower” of the Granada Native Garden Newsletter to keep in touch with some of the amazing features in the Garden, by clicking the “Follow” button that (usually) appears at the lower right corner of your screen! Quote du jour

Quote du jour  “We need the tonic of wildness. At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature.” – Henry David Thoreau

“We need the tonic of wildness. At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature.” – Henry David Thoreau

Check out the native plant selection at ALDEN LANE NURSERY, 981 Alden Lane, Livermore, CA 94550

Plants in 4-inch pots

Plants in 4-inch pots

1-gal and larger plants

1-gal and larger plants

For reliable certified arborist services, contact STUMPY’S TREE SERVICE, (925)518-1442, http://www.stumpystrees.com .

Guided Tours of the Granada Native Garden Are Available! Are you interested in seeing some of the plants that are described in this News- letter or in past issues? One or more staff of the GNG are routinely on duty at the Garden on Mondays and Thursdays, roughly between 10:00 AM and 12:00 noon. But it isn’t very hard to arrange a guided visit at other times. If you are interested in scheduling a visit, just email Jim at JIMatGNG@gmail.com . Or if you have any questions or inquiries, please email Jim at the same address!

Guided Tours of the Granada Native Garden Are Available! Are you interested in seeing some of the plants that are described in this News- letter or in past issues? One or more staff of the GNG are routinely on duty at the Garden on Mondays and Thursdays, roughly between 10:00 AM and 12:00 noon. But it isn’t very hard to arrange a guided visit at other times. If you are interested in scheduling a visit, just email Jim at JIMatGNG@gmail.com . Or if you have any questions or inquiries, please email Jim at the same address!

Flannelbush – Look But Don’t Touch! Commuters or citizens traveling southward along Murrieta Drive in Livermore at this time of the year can hardly avoid noticing the parade of flannel bushes (Fremontodendron sp.) that line the west side of the boulevard along the eastern border of the Granada Native Garden. They announce the arrival of spring at the Granada Native Garden, and beckon the curious to take a closer look at these native California wonders! Indeed, the flannel bushes are among the California native plants most commonly inquired about by visitors to the GNG. But before you are tempted to fall in love with these beauties, read on!

Flannelbush – Look But Don’t Touch! Commuters or citizens traveling southward along Murrieta Drive in Livermore at this time of the year can hardly avoid noticing the parade of flannel bushes (Fremontodendron sp.) that line the west side of the boulevard along the eastern border of the Granada Native Garden. They announce the arrival of spring at the Granada Native Garden, and beckon the curious to take a closer look at these native California wonders! Indeed, the flannel bushes are among the California native plants most commonly inquired about by visitors to the GNG. But before you are tempted to fall in love with these beauties, read on!  Major General John C. Fremont (1813-1890) was an American soldier, explorer, politician and controversial but unsuccessful candidate for the presidency. A former governor of Arizona, he is well known for historical discoveries and expeditions throughout California. Less known is that he also had a life-long interest in science and botany, which led to his name being given to the genus to which flannelbush is assigned.

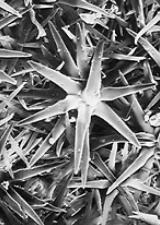

Major General John C. Fremont (1813-1890) was an American soldier, explorer, politician and controversial but unsuccessful candidate for the presidency. A former governor of Arizona, he is well known for historical discoveries and expeditions throughout California. Less known is that he also had a life-long interest in science and botany, which led to his name being given to the genus to which flannelbush is assigned. John Fremont — A Prickly Personality? Fremont’s personality has been described by his biographers as “controversial, impetuous, and contradictory” – a military hero of significant accomplishment, but marred by an ambitious drive for success, self-justification, and passive-aggressive behavior. One biographer believed that Frémont lived a dramatic lifestyle, one of remarkable successes, and one of dismal failures. One might also describe it as “prickly”, which is defined as “covered with sharp spines”, because this also happens to describe his namesake, the flannelbush. A flannelbush “in full bloom is unforgettable”. Personally, I find flannel to be soft, warm and comforting, like my winter pajamas! But brush up against flannelbush and you will soon find yourself itching and scratching. The underside of the flannelbush foliage, as well as other parts of the plant, is densely covered with fine hairs that superficially resemble flannel, as shown in this photo of a petiole by Debbi Brusco. But a microscopic view of these hairs, as in the photo by Sherwin Carlquist, reveals that the hairs have stiff, stellate (star-shaped) tips that point in all directions. These hairs easily become embedded in the skin and cause the itching and scratching — so much so that, if you need to work among flannelbush, it is recommended that you save this task for the last, so that you can go home and change your clothes and take a shower!

John Fremont — A Prickly Personality? Fremont’s personality has been described by his biographers as “controversial, impetuous, and contradictory” – a military hero of significant accomplishment, but marred by an ambitious drive for success, self-justification, and passive-aggressive behavior. One biographer believed that Frémont lived a dramatic lifestyle, one of remarkable successes, and one of dismal failures. One might also describe it as “prickly”, which is defined as “covered with sharp spines”, because this also happens to describe his namesake, the flannelbush. A flannelbush “in full bloom is unforgettable”. Personally, I find flannel to be soft, warm and comforting, like my winter pajamas! But brush up against flannelbush and you will soon find yourself itching and scratching. The underside of the flannelbush foliage, as well as other parts of the plant, is densely covered with fine hairs that superficially resemble flannel, as shown in this photo of a petiole by Debbi Brusco. But a microscopic view of these hairs, as in the photo by Sherwin Carlquist, reveals that the hairs have stiff, stellate (star-shaped) tips that point in all directions. These hairs easily become embedded in the skin and cause the itching and scratching — so much so that, if you need to work among flannelbush, it is recommended that you save this task for the last, so that you can go home and change your clothes and take a shower! Guided Tours of the Granada Native Garden Are Available! Are you interested in seeing some of the plants that are described in this News- letter or in past issues? One or more staff of the GNG are routinely on duty at the Garden on Mondays and Thursdays, roughly between 10:00 AM and 12:00 noon. But it isn’t very hard to arrange a guided visit at other times. If you are interested in scheduling a visit, just email Jim at JIMatGNG@gmail.com . Or if you have any questions or inquiries, please email Jim at the same address!

Guided Tours of the Granada Native Garden Are Available! Are you interested in seeing some of the plants that are described in this News- letter or in past issues? One or more staff of the GNG are routinely on duty at the Garden on Mondays and Thursdays, roughly between 10:00 AM and 12:00 noon. But it isn’t very hard to arrange a guided visit at other times. If you are interested in scheduling a visit, just email Jim at JIMatGNG@gmail.com . Or if you have any questions or inquiries, please email Jim at the same address!